Redfish brief recap

Redfish® is a low-level management RESTful API standardized by the Distributed Management Task Force (DMTF) consortium. DMTF publishes several standards related to server management, like the Common Information Model (CIM) implemented as OpenPegasus on Linux and Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) on Microsoft Windows.

Redfish was first introduced in August 2015. As of today, more than sixty members contribute to its development: computer makers, storage and network device manufacturers and software developers. A funny story relates how "Redfish" comes from the name of a restaurant near the Compaq drive in Houston, Texas, where initiators of the project were meeting before DMTF took over the entire project.

The main reason Redfish was introduced was to replace the Intelligent Platform Management Interface (IPMI) originally created by Intel®. In a nutshell, Redfish is able to monitor, configure and perform actions (i.e. power-on/off) on remote (out-of-band) or local (in-band) servers. Also, it provides an event subscription mechanism that can replace the Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP).

The adoption of this standard across the industry has been very quick and this article is an attempt to explain some of the specificities that have contributed to its success.

Redfish specificities

Redfish is classified as a RESTful API as all the fundamentals are present, like a client/service model and HTTPS JSON formatted requests transferring representational states from and to identified end points. However, several specificities are unique, like the separation of the protocol and the data model and the possibility to enhance the data model with Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) extensions.

Client/service architecture

The Redfish service is included in the server management controller firmware and cannot be separated from it. In this article, I will name this controller “BMC”, for “Baseboard Management Controller”. Every modern server worthy of the name has a BMC that starts as soon as an electrical cable is plugged into a power supply. Internally, the BMC communicates with most server subsystems (BIOS, network controllers, storage, power supplies, fans, etc.). It can communicate with the operating system as well, either through a proprietary protocol or a host interface. Externally, the BMC includes a network connector that allows it to communicate with other network services (DHCP, SMTP, SNMP, etc.). At HPE, this BMC is called “HPE iLO”, at AMI it is OpenBMC, at Dell iDRAC…

Redfish clients are numerous and varied. For development and troubleshooting, the Postman API platform is very popular. For one-off actions or “quick and dirty” scripts, cURL, PowerShell, Python or even HPE iLOrest do the trick. For more sophisticated client programs, you can use an Ansible playbook library, Chef or Go and its Go-Redfish library.

Proprietary monitoring applications (i.e., HPE Compute Ops Management) or open source applications (ODIM, Nagios, etc.) constitute native Redfish clients or can become so using specific plugins.

Remote or local management

In most cases, Redfish clients perform out-of-band management. However, it is entirely possible to install the client in the OS of the server to be managed and to access the BMC via an internal path to the server (in-band-management). This path can be proprietary like HPE's CHIF (Channel Interface) or the Ethernet over USB protocol, which allows an IP connection between the OS and the BMC.

Protocol and data model separation

The Redfish protocol specification is published in DMTF document DSP0266, while data modeling is in DSP0268. This separation allows flexibility with regard to the management of version numbers. Without this separation, a minor change to the protocol specifications (e.g. adding an acronym to the glossary) would involve an increment of the overall specification version number and impose a set of unnecessary tests to re-qualify clients.

What’s inside the protocol specification?

- Boring but necessary topics like the normative framework (definitions, symbols, glossary, typographical conventions, etc.).

- Things a little more interesting like compliance with other standards (Open Data, Swagger/OpenAPI, etc.).

- We also find some very practical things like the ways to authenticate (basic authentication, session token, etc.) and the endpoints where authentication is necessary (everywhere except at the root

/redfish/v1). - Surprising things like receiving an "error" message for successful requests. Figure 2 shows the successful erasure of a storage logical volume (LUN) whose response contains the

error{}object with a message explaining the success of the operation! This type of incongruous response is a consequence of compliance with the Open Data standard.

Data model

Responses to Redfish requests consist of JSON packets containing key/value properties defined by the DMTF in a schema file. The name of the schema file describing responses is contained in the @odata.type property that must be present in each response.

For example, the schema defining the root of the Redfish tree is #ServiceRoot. Its full name returned by curl -sk https://bmc-ip/redfish/v1 | jq '."@odata.type"' is: #ServiceRoot.v1_13_0.ServiceRoot. Appended to the #ServiceRoot fragment, a version number (1_13_0) and then a subtype that, in this specific case, is identical to the main schema. All schemas are publicly available on the DMTF website and, are sometimes included in the service itself (refer to the Self Describing Model paragraph below). Note that schema versions can evolve independently of each other.

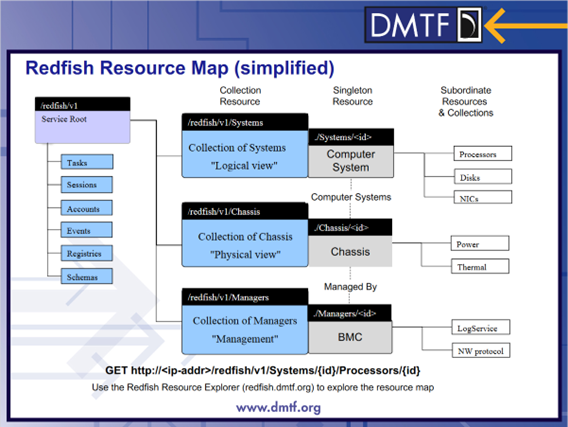

With a close look to the Redfish root diagram in (Figure 3), you will notice the presence of endpoints allowing access to the modeling of the server subsystems. For example, the Chassis{} object points to /redfish/v1/Chassis, which contains the exhaustive collection of URIs (./{ChassisId}) modeling the different chassis constituting the server (racks, blades, enclosures, storage enclosures, etc.).

OEM extensions

Computer makers are able to model proprietary properties (not standardized), which constitutes added value compared to the competition. For example, HPE iLO can store firmware updates before deploying them to their respective components. This specificity is described in the proprietary schema #HpeiLOUpdateServiceExt present in the Oem.Hpe{} object under the URI /redfish/v1/UpdateService (Figure 4).

OEM extensions can also be used by a manufacturer while awaiting the standardization of a functionality unanimously recognized by DMTF members.

Resource collections

As shown in figure 3 above, links contained in the Redfish root tree, do not provide direct access to the properties of the server subsystems. Instead, they point to “resource collections”. The collection members are described by a unique schema. For example, the response to the GET /redfish/v1/Chassis request made against the BMC of an HPE Superdome consisting of 2 chassis in a rack, is a collection containing four members: RackGroup, Rack1, r001u03b and r001u08b (Figure 5). These four members have the #Chassis diagram in common.

Another example: An HPE ProLiant server containing a storage enclosure connected to a (“modern”) storage controller is represented by two members in the chassis collection; a member pointing to the chassis containing the motherboard of the server (/redfish/v1/Chassis/1) and a member pointing to the backplane of the storage enclosure (/redfish/v1/Chassis/DE040000).

Each member of the collection is an endpoint for accessing the member properties. Links to related resources constitute transversal access to other subsystems. For example, the storage chassis in Figure 6 contains a cross-link to the storage device under the "Systems" tree (/redfish/v1/Systems/1/Storage/DE040000).

Naming convention of collection members

The naming of collection members is specific to each implementation of the Redfish service. The BMC endpoint for an HPE ProLiant is: /redfish/v1/Managers/1. That of an OpenBMC is: /redfish/v1/bmc and that of a Superdome is /redfish/v1/Managers/RMC. Dell, SuperMicro, Lenovo probably have their own way of naming their BMCs, while remaining compliant with the specifications.

The naming flexibility given to Redfish services generates extra work for client developers: their code has to discover the names of collection members before being able to access their properties. If they assume a specific URI, their code will fail when used against another computer maker or after a firmware update.

Registries

The data modeling described above don't represent resources that have inter-dependencies (i.e., BIOS attribute %1 depends of attribute %2) as well as information or error messages and their arguments (e.g.: "error on disk %s in location %s"). To address this problem, Redfish uses "registries".

Figure 7 is extracted from a BIOS registry that has the effect of prohibiting the activation of Windows secure mode support if the server does not contain a TPM (Trusted Platform Module). It is interesting to note that the BIOS registry also describes the GUI menus (MapToProperty=GrayOut).

Figure 8 is taken from the base message registry. It shows the modeling of the “Access prohibited” message with the name of the prohibited resource as an argument (%1).

Self-describing model

Redfish is considered "self-describing" because the information regarding data modeling, operations and possible actions is documented and programmatically accessible. Client programmers no longer have to consult paper specifications before implementing them. They can transfer this task to their code in order to ensure a certain portability in time and space.

The benefits of this "hypermedia API" concept are explained in this blog post

Accessing Schemas and registries

Redfish provides access to schemas and registries through the following endpoints:

/redfish/v1/JsonSchemas/redfish/v1/Registries

These URIs contain links to all schemas and registries used by the service. They point to documents stored in the BMC, if it has the storage capacity, or to the official DMTF website. In the latter case, Redfish clients must have a means to access the Internet to download those documents. They are helpful to identify property inter-dependencies, supported values or read-write capability.

Allowed requests

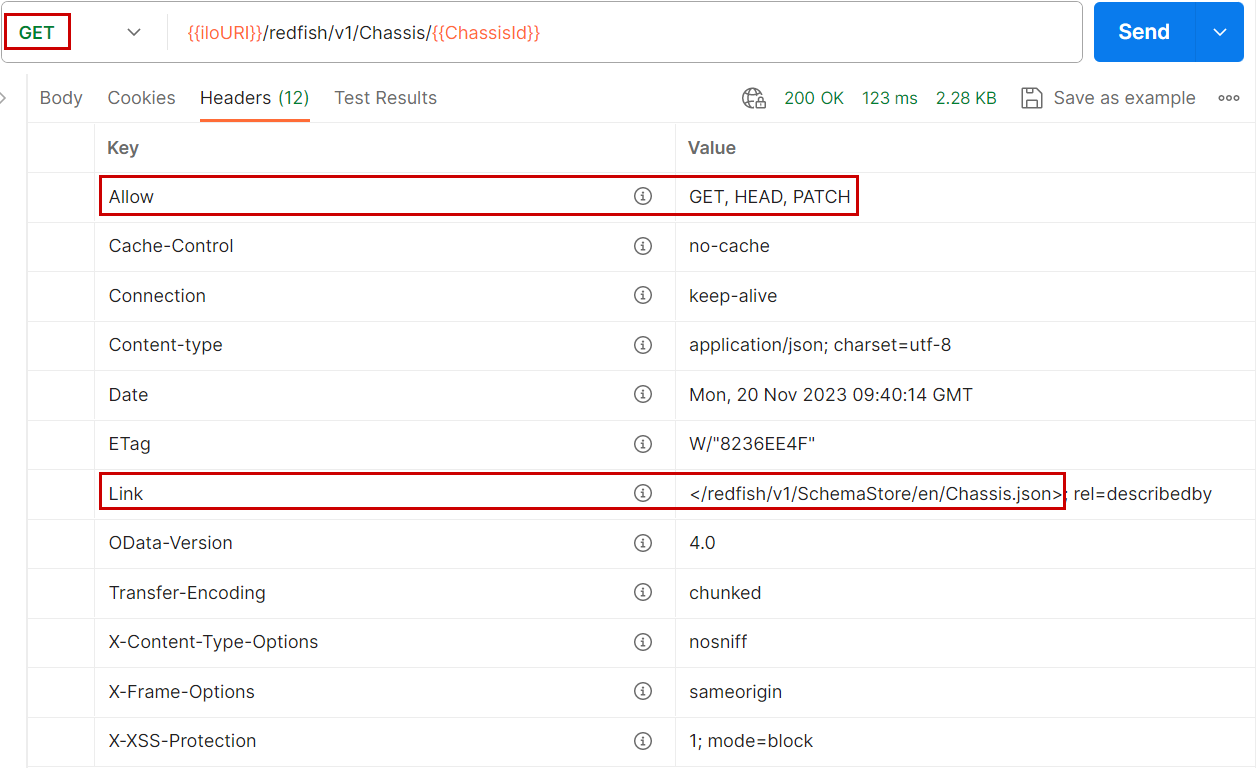

The Redfish protocol requires GET request responses to contain the Allow header indicating the possible operations on the URI. Figure 9 shows that the URI /redfish/v1/Chassis/{ChassisId} allows GET, HEAD, and PATCH operations against this URI.

After verification, the client code can change (PATCH) the properties marked as ReadOnly=False in the schema. The main server chassis in Figure 9 shows the PATCH method and the IndicatorLED property can be modified (Figure 10), so one should be able to turn on the small blue LED on this chassis to better identify it in the data center. A good programmer will perform all of these checks before sending their changes. The bad programmer will not perform any checks and will leave the end user to deal with the error(s) returned by the service!

Link to schema

To help client programmers to verify programmatically property descriptions, the protocol imposes a header Link in responses, pointing to the concerned schema file, as shown in Figure 9. With such a link, clients don't have to browse the schema and the registry stores mentioned above; they just have to follow the provided link.

Deprecated resources

Over time, certain properties are deprecated. This information is mentioned in the schemas. Thus, clients receiving a “property not found” response will be able to consult the schema and check if by chance this property has not been deprecated. This type of verification will avoid comments from the programmer like "I don’t understand, it worked before!". But before what? Figure 10 shows an excerpt from the #Chassis schema, version 1.22.0, stating that the IndicatorLED property has been deprecated in version 1.14.0.

What else?

The separation of protocol from data modeling, collections, OEM extensions and registries form the basis of the Redfish standard. Access to schemas and registries as well as the list of possible operations for each URI are important features allowing the writing of portable client code in time and space.

However, Redfish is full of other particularities, conceptual and practical, which are very interesting to study. For example the mode of communication with storage and network cards, firmware updates, or even the use of Swordfish® schemas developed by the Storage and Network Industry Association (SNIA) are only a few of them. Many security aspects are also addressed by Redfish such as the integrity of the various server components. Read the second part of this Redfish introduction for a complete view of this standard API.

Don't forget to check out some of my other blog posts on the HPE Developer portal to learn more about Redfish tips and tricks." target="_blank">second part</a> of this Redfish introduction for a complete view of this standard API.

Don't forget to check out some of my other blog posts on the HPE Developer portal to learn more about Redfish tips and tricks.

Related

Benefits of the Platform Level Data Model for Firmware Update Standard

Jun 7, 2022

Build your own iLO Redfish simulator

Jun 11, 2021

Discover the power of data center monitoring using Redfish telemetry and cloud-native tooling: Part 2 - Streaming

Dec 1, 2023

Discover the power of data center monitoring using Redfish telemetry and cloud-native tooling

Oct 5, 2023

How to change the factory generated iLO Administrator password

Mar 29, 2018